The internet has spoken, and the future of video delivery is GIF.

Here at Brightcove, we have been experimenting with a plethora of technologies around the GIF format. One such experimental technology is called GIF+A (pronounced gifta) where audio is embedded into the video frames by using a portion of the color palette to invisibly encode an AAC audio bitstream into the pixel data.

Another experiment, undertaken by our Once team, involves transcoding both video and flash based advertisements into GIFs before delivering them to the user. This means that the transcoded ads can play anywhere, and are far less likely to trigger ad blockers.

However, of all our experimental technologies, the most exciting development is HTTP GIF Live Streaming - HGLS. In HGLS, we utilize Zencoder to generate segmented GIF live streams from an RTMP input.

One Source. Any Browser.

Like HLS, which HGLS supersedes, we specify the segments within a text file called a playlist. The player periodically re-requests the playlist from the server to learn about new segments. The segments are requested and played, in sequence, providing for a low-latency live stream experience delivered over standard HTTP.

HGLS brings many benefits over other video container technologies. The most important difference is reach. HGLS can be viewed in any browser that supports animated GIFs in the IMG element. We had one live stream playing for days on a cluster of Windows 95 OSR2 machines running Netscape Navigator 2 without any issues.

Reach is an important part of digital marketing and advertising. With HGLS, you can deliver ad-supported video to 99.997% of all internet users without requiring the use of evergreen browsers or the installation of any plugins.

Playback of HGLS presents two interesting challenges from a technical perspective. One is that a raw IMG element doesn't act like a video element, lacking the functions and events we have all come to love. To solve this issue, Brightcove developed a Video.js tech (videojs-contrib-image) that wraps an image element and emulates video element events and functions.

The second problem is more insidious. The proliferation of limited-reach video containers such as MP4 and WebM has conditioned users to expect certain capabilities from their player. People demand the ability to pause and perform frame-accurate seeks. These behaviors are simply not possible using IMG elements because there is no way to control the intricate playback engine of a GIF.

Enter Media Source Extensions

One solution would be for browser vendors to add GIF support to the video element itself - something several browser vendors are planning to support in upcoming releases. At Brightcove, we decided to use a system of progressive enhancement to gain the future benefits of native GIF support today.

What this means to users is that they get a video experience optimized for their browser. If they are running an older browser, we use IMG elements, but they lose the ability to pause or seek (except at segment boundaries). If they are using a modern browser, we playback GIFs in a real video element by utilizing Media Source Extensions.

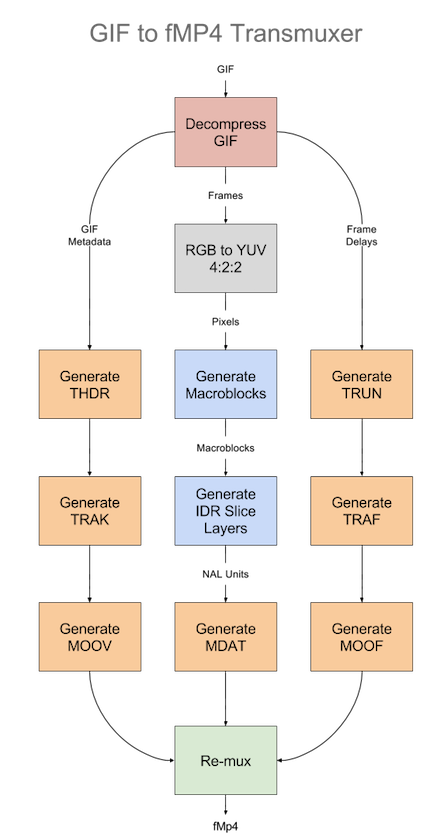

Within videojs-contrib-media-sources and mux.js we created a transmuxer pipeline that appears to the outside world as a SourceBuffer. It is able to accept GIF-encoded video in the appendBuffer function. The transmuxer then converts GIFs into fragmented MP4s containing H.264 bitstreams that consist of only i-frames. We take the resultant fragment and append them to a real native SourceBuffer.

The transmuxer operates in a web worker and uses the gifuct-js library to decompresses the GIF frames into RGB buffers while saving the frame delay values to an array. Then we convert the raw RGB planes into YUV planes while simultaneously downsampling U and V planes to generate the YUV:422 frame data that H.264 expects.

The final step for generating an H.264 bitstream involves generating I_PCM macroblocks for the image data and placing the macroblocks into an IDR slice layer NAL unit. The rest of the pipeline simply package the NAL unit into MP4 boxes (or atoms) to generate a valid fMP4 output. The output is fed directly into a MediaSource and played directly by the video element without any other manipulation.

We hope the world gets to experience this bleeding edge live playback technology in the near future, and are welcome to ideas for enhancements in the Video.js Slack channel.